By Jim English

While diabetes is the leading cause of kidney failure, blindness and lower limb amputations not caused by accidents or trauma, the most serious threat facing diabetic patients is death from heart attack or stroke. Eighty percent of hospitalizations for patients with diabetes are for macrovascular disorders, such as coronary disease, cerebrovascular disease and peripheral vascular disease, and 75 percent of deaths in diabetics are cardiovascular death, mostly in patients with Type 2 diabetes. To put these numbers in perspective, while a 50-year-old patient with “average” blood pressure and cholesterol levels has a 7 percent chance of experiencing a heart attack in the next 10 years, a 50-year-old diabetic patient faces up to a 50 percent chance of having a heart attack in the next ten years.

ACCORD Trial Fails to Protect Diabetic Patients

In 2001, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) launched a trial to lower blood glucose levels in diabetic patients to reduce their risk for heart attack, stroke, or death from cardiovascular disease. The trial, called Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes, or ACCORD, involved over 10,000 Type 2 diabetic patients who had either been previously diagnosed with heart disease or had two or more risk factors for heart disease when they entered the study.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of two treatment groups. The first group of 5,123 participants was treated with standard drugs and insulin at levels generally approved as the standard for Type 2 diabetes. The second group, consisting of 5,128 participants, was assigned to receive a much more aggressive form of treatment involving higher doses of the standard therapy. For both groups, study clinicians were permitted to use all major classes of FDA-approved diabetes medications, including metformin, thiazolidinediones (TZDs, primarily rosiglitazone), insulins, sulfonylureas, exanatide, and acarbose. Treatment goals in both groups were determined throughout the study by regular blood tests that measured patient A1C levels.

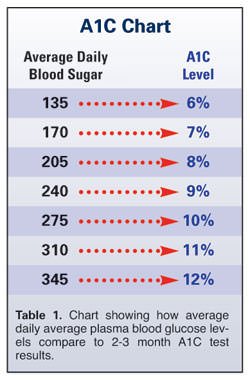

The A1C blood test gives diabetic patients an accurate way of monitoring glucose levels to better manage their blood sugar control. A1C, also known as glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), is produced when glucose molecules become attached to hemoglobin – the oxygen-carrying protein found in red blood cells – in a process called glycosylation. The percentage of glycated hemoglobin in the blood stream increases as blood cells are exposed to elevated sugar levels over time. Since red blood cells can live for up to 120 days in the body, testing for A1C levels can aid patients and practitioners in looking back to accurately gauge average blood sugar levels for the previous 2 to 3 months.

While healthy people commonly have A1C levels as low as 5 percent (i.e., only 5 percent of their hemoglobin is glycated), diabetics frequently with have A1C levels as high as 8 or 9 percent (Table 1). According to the American Diabetes Association, in extreme cases A1C levels can go as high as 25 percent when diabetes is poorly controlled for long periods.

A1C and Advanced Glycation End Products (AGEs)

In addition to measuring glycosylated hemoglobin, the A1C test can also indirectly reveal the presence of other damaging compounds produced in the presence of high blood sugar levels. These abnormal compounds, known as advanced glycation end products (AGEs), are produced by the same non-enzymatic process that binds sugar to blood cells. By binding sugar with other proteins, lipids and nucleic acids, AGEs alter the structure and function of various cells and tissues throughout the body to promote damage to blood vessels, peripheral nerves and organ tissues.

AGEs have been shown to accelerate atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), contributing to an increase in the risk of a heart attack or stroke. In patients with chronic diabetes, AGEs are also implicated in peripheral vascular disease (which can cause gangrene and lead to amputations), peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage in the limbs), retinopathy (eye damage) and nephropathy (kidney damage). A simple A1C blood test can directly determine which patients are most at risk by measuring the advanced glycation endproducts of normal hemoglobin (HgB).

Pushing Patients to The Brink of Disaster

The standard treatment goal for the control group was to maintain a target A1C of 7 to 7.9 percent, similar to A1C levels normally seen in diabetic patients following current diabetes protocols. By contrast, the goal of the intensive drug treatment test group was to increase insulin and drug dosages to aggressively push blood sugar levels down to A1C levels of less than 6 percent, similar to levels normally seen in healthy adults without diabetes. In addition to increasing deaths in the intensive drug treatment group, less than half of the participants succeeded in getting their A1C level below 6.4 percent.

The decision to halt the ACCORD trial 18 months prior to its scheduled completion became necessary after an interim NIH review revealed a 26 percent increase in deaths in the aggressively treated patient group (257 deaths), versus the standard drug therapy group (203 deaths). Additionally, while the agency noted a 10 percent drop in heart attacks among aggressively treated patients when compared to the general diabetic population (likely due to the extra level of health care and monitoring the patients received while taking part in the program), when a heart attack did occur it was more likely to be fatal in the study group. According to Dr. William Friedewald of Columbia University, who helped monitor the study, “In addition, the intensive treatment group had more unexpected sudden deaths, even without a clear heart attack.”

Rush to Calm Fears Over Diabetes Drugs

Even as the NIH cautioned that it didn’t know the reason for the unexpected deaths, the agency moved with impressive speed to calm patient fears over the use of multiple diabetic medications, stating, “Based on analyses conducted to date, there is no evidence that any medication or combination of medications is responsible.” In their announcement the NIH also addressed the use of the drug rosiglitazone (Avandia), claiming, “Because of the recent concerns with rosiglitazone, our extensive analysis included a specific review to determine whether there was any link between this particular medication and the increased deaths. We found no link.”

The rush by the NIH to exonerate drugs for any causative role in the unanticipated deaths strikes some observers as odd, given that the only notable difference between the two treatment groups was the quantity of FDA-approved diabetic medications given to the participants. Even more troubling was the suggestion by lead investigators from the trial that the concept of glucose control in patients with Type 2 diabetes may not even be desirable.

While the ACCORD trial aimed to save lives, the study continues to come under criticism from clinicians and patients for its intense focus on pharmaceutical intervention and lack of support for less dangerous options. While study participants were closely monitored to insure that they adhered to the rigorous treatment plan that, in some cases, had patients checking blood sugar levels throughout the day and taking four or five shots of insulin, there was no similarly stringent requirement or support system in place to encourage alternative, non-pharmaceutical strategies for controlling blood glucose levels, and inclusion of moderate exercise or dietary control were left up to the patients.

Deadly Overreliance on Drug Intervention

Commenting on the outcome of the failed ACCORD trial in the online, peer-reviewed journalNutrition and Metabolism, Eric Westerman, Department of Medicine, Duke University Medical Center states, “From our perspective of familiarity with dietary carbohydrate-restriction and diabetes, these results are not surprising – in fact, they are predicted. We believe that it is unlikely that the increased mortality was due to the tight glucose control but rather due to the particular method for trying to achieve it.

When high carbohydrate diets are consumed and intensive medication therapy is used to ‘cover the carbohydrate,’ it is very difficult to achieve normal glycemic control without hypoglycemic reactions. In our clinical practices, we frequently see individuals who are instructed to eat high carbohydrate diets and use intensive injectable hypoglycemic therapy, and they are susceptible to hypoglycemic reactions. Severe hypoglycemic reactions are associated with an increased morbidity and mortality.”

Despite widespread media reports to the contrary, the ACCORD trial was a large-scale human drug experiment that tragically backfired. And while diabetic patients and physicians await a final report from the NIH, the most obvious lesson of the trial appears to be that piling increasingly high dosages of blood-sugar lowering drugs and insulin on already weakened, at-risk patients is a bad idea.

The outcome of the study is especially troubling given that many, if not most, Type 2 diabetic patients can achieve the goals targeted by ACCORD by adopting a broader, integrative approach that includes reduced intake of dietary carbohydrates, regular physical exercise, and when necessary, moderate use of drugs and insulin.

Herbal Blood Sugar Formula Shown to Support Blood Sugar Control, Improves A1C

Dr. Chuang is a researcher with experience in treating diabetes with both Western drugs and Chinese herbs. He is also a Type 2 diabetic who has successfully brought his own blood sugar levels into normal range using an advanced herbal formula. The unique selection of herbal ingredients in Dr. Chuang’s formula has been shown to support pancreatic function, glucose metabolism and energy production. In addition to reversing metabolic and chemical disturbances generated from long-term exposure to elevated insulin and blood glucose levels, this herbal blend can also assist in controlling food cravings, particularly hard-to-resist carbohydrate cravings, to support safe and natural weight loss.

Professional Feedback on Dr. Chuang’s Herbal Blend

In our January, 2007 issue of Nutrition Review, Mitch Fleisher, MD reported on the results of his evaluation of Dr. Chuang’s formula, writing:

“Several of my patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) have benefited significantly from Dr. Chuang’s herbal formula. Following four months of daily use (three capsules three times daily), blood tests revealed a significant reduction in fasting blood sugar levels in my patients – in some cases dropping as much as sixty points. By reducing blood sugar, Dr. Chuang’s formula aids in bringing serum glucose levels down to a much more acceptable range for long-term medical management.”

“Of greater significance, blood tests have shown that Dr. Chuang’s formula also aids in restoring hemoglobin A1C (HgbA1C or glycosylated hemoglobin) levels to a more normal range. A1C is a relative measurement that determines average blood sugar levels over the previous three months to aid clinicians in determining a patient’s degree of insulin resistance and sustained hyperglycemia (high blood sugar). An A1C value of 7.0 or greater represents poor blood sugar control. In this regard, I have observed that patients taking Dr. Chuang’s formula experience, on average, a restoration of A1C values down into the 5.4 to 6.2 range. These numbers signify a significant reduction in sustained hyperglycemia, diminished insulin resistance and improved diabetic control.”

Client Feedback on Improved A1C Test Scores

In our July, 2007 newsletter we shared the following letter from Myrna, detailing how she and her husband Harold improved their A1C scores with Dr. Chuang’s formula.

I am writing to tell you about our continued success with Dr. Chuang’s formula. When we first started taking the formula over a year ago our morning blood sugar measurements dropped from the high 140’s down to about 110 when taking 2 capsules, twice daily. Harold had lost about 15 pounds and I lost about 8. Both of us noticed that our food cravings were slightly reduced, which is amazing since neither of us are great dieters.

Most importantly, prior to taking Dr. Chuang’s formula our A1C levels were both around 7.5, which our doctor was very concerned about. Then, after six months on Dr. Chuang’s formula Harold’s A1C dropped to 6.9, and mine was down to 7.1.

Now, a year after those last results, we have just received the latest A1C numbers from our doctor. To our delight, Harold’s A1C has dropped again, and is now down to 5.4, the lowest level ever. My A1C is down to 6.3. I must admit that I have not been as diligent about taking the formula as Harold has been, and the results show.

Regards, Myrna S.

Note: Type 2 diabetics using Dr. Chuang’s formula to control blood sugar levels may also experience improvement in related morbidity factors, including hypertension, hyperlipidemia, nephropathy and neuropathy. Patients with these conditions should continue to be monitored by their physician for changes in their condition and modify medications as necessary.

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]

[…] In one large study, called the ACCORD study, that was published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2008, the 10,000 patients who were being treated with insulin or blood sugar-lowering drugs were monitored and evaluated for their risk of heart attack, strokes and death. The National Institutes of Health ended the study early because the medical intervention was leading to MORE deaths, heart attacks, and strokes. […]