By Jim English and Ward Dean, MD (Published May, 2003)

The recent appearance of a new lethal infectious respiratory disease is naturally a cause for concern and apprehension. SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) is continuing its global spread as we prepare to send our newsletter off to the printer. To date, since emerging from an agricultural community in China, SARS quickly spread across the globe, infecting at least 3,235 people in 22 countries and killing 161 people worldwide, mostly in Asia.

New medical updates – seemingly released every few hours – are helping researchers better understand the epidemic, but often one announcement simply contradicts the details of a previous finding. One day the outbreak in China is under control, the next brings a batch of fresh cases and newfound fears of ‘super spreaders.’ A prime example is that shortly after declaring the outbreak under control, Hong Kong authorities were hit with forty new cases and nine deaths in a single day.

In response to the epidemic, people in affected regions are rarely seen without a surgical mask, and those outside affected areas are staying away. Airlines have cancelled flights to and from Asia, schools have been closed, and residents of apartment complexes that housed infected patients are being moved to quarantine camps – all in a desperate bid to halt the spread of SARS. In hard-hit Canada, health authorities have taken the extraordinary step of closing hospitals while isolating anyone showing signs of infection.

Given the seriousness of the situation and the rapidly changing stream of information, our purpose in this article is to focus on the current known facts concerning SARS and to suggest potentially preventative and therapeutic options.

A New Coronavirus

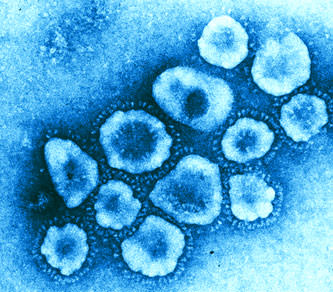

Since emerging from mainland China a month ago, SARS has been identified as a new form of coronavirus, so named for the halo of blobby protein spurs surrounding the viral envelope (Fig. 1).

Coronaviruses are not new, as other types of this virus are known to cause colds and respiratory illnesses that may develop into bronchitis and pneumonia. What makes SARS unique is that this species has not been seen before – a fact that complicated early attempts to find a treatment for the disease.

Researchers in Canada have just announced the sequencing of the viral genome, which will greatly aid development of diagnostic test kits for rapid identification of the illness. Additionally, researchers in the Netherlands have confirmed that monkeys infected with the coronavirus develop the same symptoms as humans do – an important finding required to verify that this virus is the actual causative agent.

SARS Symptoms

According to the CDC, SARS begins with a high fever (greater than 100.4¡ F [38.0¡ C]) and flu-like symptoms that can include headache, an overall feeling of discomfort, and body aches. Some people also experience mild respiratory symptoms. After two to seven days, SARS patients may develop a dry cough and have trouble breathing. Symptoms often progress to a severe form of pneumonia.

How SARS Spreads

SARS appears to be spread primarily by close person-to-person contact. Most cases of SARS involved people who cared for or lived with someone with SARS, or had direct contact with infectious material (for example, respiratory secretions) from a person who has SARS. Potential ways in which SARS can be spread include touching the skin of other people or objects that are contaminated with infectious droplets and then touching your eye(s), nose, or mouth. This can happen when someone who is sick with SARS coughs or sneezes, spreading the virus to other people or to nearby surfaces. It also is possible that SARS can be spread more broadly through the air, by fecal material, or by other means that are currently not known.

Who is at Risk for SARS

Cases of SARS continue to be reported mainly among people who have had direct close contact with an infected person, such as those sharing a household with a SARS patient and health-care workers who did not use infection control procedures while taking care of a SARS patient. One troubling aspect of SARS is that, unlike influenza and other viral diseases that mostly threaten the very young and the elderly, SARS is also infecting young adults (under 45 years) who have relatively healthy immune systems. And recent reports from Hong Kong indicate that the virus is mutating, and researchers fear that the changes are making the disease more severe.

Orthodox Treatment for SARS

Currently there is no clear treatment for SARS. Antibiotics are ineffective, and patients are reportedly not being helped with standard antiviral drugs. Aside from putting patients on respirators to assist lung functions, the only response left is to make the patients comfortable while isolating them to contain and control the epidemic.

Alternative Treatment Options

Since SARS is caused by a virulent virus that is unresponsive to available treatments it seems reasonable to use a combination of antivirals and immune enhancers to protect those at risk, or even to treat those who may be infected.

Consequently, the first thing we recommend is to use a cool mist humidifier, filled with a solution of one bottle of 3 percent hydrogen peroxide, and two bottles of water. This provides a one percent aerosolized mist of hydrogen peroxide. Just fire up the humidifier and run it in the bedroom at night, and in the home or office during the day. Usually, one or two days may be all that is required to alleviate a number of pulmonary infections, ranging from the common cold to pneumonia. Hydrogen peroxide is a very effective anti-microbial, and virtually kills the bugs on contact. Overuse (more than a few days of continuous use) may result in bleaching of the hair, although this would be a minor inconvenience compared to the potential adverse consequences of SARS.

Second, we suggest Mild Silver Protein 400 ppm. MSP is also a powerful virucidal substance. Based on reports from physicians who have treated patients suspected to have SARS, high doses of MSP are required, i.e., one tablespoon per hour until symptoms begin to resolve. This usually requires several days. UniBiotic is also designed specifically for pulmonary infections, and may provide added protection – especially in terms of preventing secondary bacterial infections. Other antiviral nutrients like Olive Leaf Extract and Garlic may also be helpful.

The other side of the preventive-therapeutic coin is to maintain the integrity of the immune system. We believe the most powerful immune enhancer is Thymic Protein A. Although the recommended dose is three envelopes daily, many of the benefits of this remarkable substance can be obtained by doses as low as one or two envelopes per week. Thymic Protein A can be augmented with other immune enhancers like Lactoferrin. N-Acetyl Cysteine (NAC) and Calcium AEP (Ca-AEP) might also be useful, for general lung health.

Conclusion

Medical scientists and health care researchers are working around the clock to contain and understand this new disease. And one has to be impressed with the speed with which researchers and epidemiologists have identified and begun to take measures to halt the spread of this virulent disease. In the span of three weeks researchers have been able to identify SARS as a new form of coronavirus, zero in on its probable source (animal) and successfully unravel its genome. This is especially impressive when one considers the years it once took to isolate and identify a single viral agent such as HIV.

Yet despite the high-tech successes in response to the SARS outbreak, there is currently no cure or effective treatment, aside from mechanical breathing support while the body defends itself against the infection.

Naturally, all of these recommendations are guesswork – but hopefully it is ‘educated guesswork.’ We think the preventive and therapeutic recommendations above are likely to be more effective than typical government recommendations like surgical masks, plastic sheeting and duct tape.

References

1. Lee, N., Hui, D., Wu., et al. A Major Outbreak of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome in Hong Kong. NEJM. Published online April 7, 2003. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/NEJMoa030685v1.

2. T.G. Ksiazek and Others. A Novel Coronavirus Associated with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome.

http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/NEJMoa030781v1.

3. C. Drosten and Others. Identification of a Novel Coronavirus in Patients with Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/NEJMoa030747v1.

4. World Health Organization.Cumulative number of reported cases (SARS)

http://www.who.int/csr/sarscountry.

5. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) updated interim case definition.

http://www.cdc.gov.