Researchers report that a common anti-malaria drug, chloroquine, has reversed cancer cells in fruit fly eyes, completely restoring the cancerous cells back into normal, healthy cells. It’s important to note that an actual reversal of a cancer has never been observed before, and its very likely that the possibility of reversing cancer cell back to normal has never even been seriously discussed beyond the purely theoretical, what-if stage. And given that the eye of a fruit fly is a particularly complex, multifaceted organ related to a significant neural system, reversing cancer and restoring function is no minor achievement.

In an op-od in the online version of Digital Journal, Paul Wallis points out that the discovery opens up a wide range of possibilities for human trials. Chloroquine is known to be safe for humans, so there are none of the usual checks and tests required prior to human testing of new drugs.

“Reversal” in this form also effectively means countering the initial mutation, which implies that the entire process of cancer development can be corrected and returned to normal health. That’s good news for those to whom the world “relapse” is a curse.

The new discovery may also cure another problem for patients and the medical profession – the huge costs and difficulties of current treatments. Associate professor and researcher Helena Richardson describes chemotherapy as a “blunt instrument”, a description which few would dispute, and it’s a very tough regime for very sick people.

A reversal process also eliminates the need for massive medical infrastructure, complex pharmaceuticals, and ever-more bizarre costs, which are doing doctors and patients no favors in terms of accessibility or the realities of treatment. This drug could be delivered anywhere in the body, safely and quickly, without the need for traumatic treatments and years of suffering.

Experts from the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne said during the trial they discovered a mutation very similar to one that a malarial parasite needs to thrive. Associate Professor Helena Richardson said by administering common anti-malarial medicine the cancerous mutation reversed. “It’s been a very exciting discovery, and very serendipitous,” Associate Professor Richardson said.

“We were studying this important protein that’s involved in cell shape regulation. We found that a mutant in this protein resulted in deregulation of cell communication.”

“From the process of analysing what was happening we found that there was a connection between what was happening inside this cancer cells and what was needed for the malarial parasite to survive in human blood cells.”

Associate Professor Richardson said researchers then treated the cancer cells in the eye of a fruit fly with the common anti-malarial drug chloroquine.

“We found that if we treated our fly with the anti-malarial drug, it completely reserved the overgrown cancer cell in the eye, and they became essentially normal again,” she said. “So this was a remarkable finding really.”

The fruit fly – Drosophila melanogaster – which was used to test the treatment, shares about 70 per cent of human disease-causing genes.

She said researchers now hoped to continue testing the method in human trials to see if the malarial medicine has the same result.

“Since this drug is relatively safe and has been used in humans to treat people who have malaria, we can essential take this drugs and if we can find the same sort of pathways are changed in human cancer, then we can treat human cancer with this drug,” she said.

She said if the drug worked it could be a much more targeted tool than chemotherapy. “In our fly model, we have found that this drug doesn’t dramatically affect any of the normal cells at all, it specifically affects the cancer,” she said.

“So if a drug can specifically target the cancer and not affect normal cells than it has a great advantage over standard chemotherapy, which is really a blunt tool.”

Source: http://ab.co/1lYkiIi

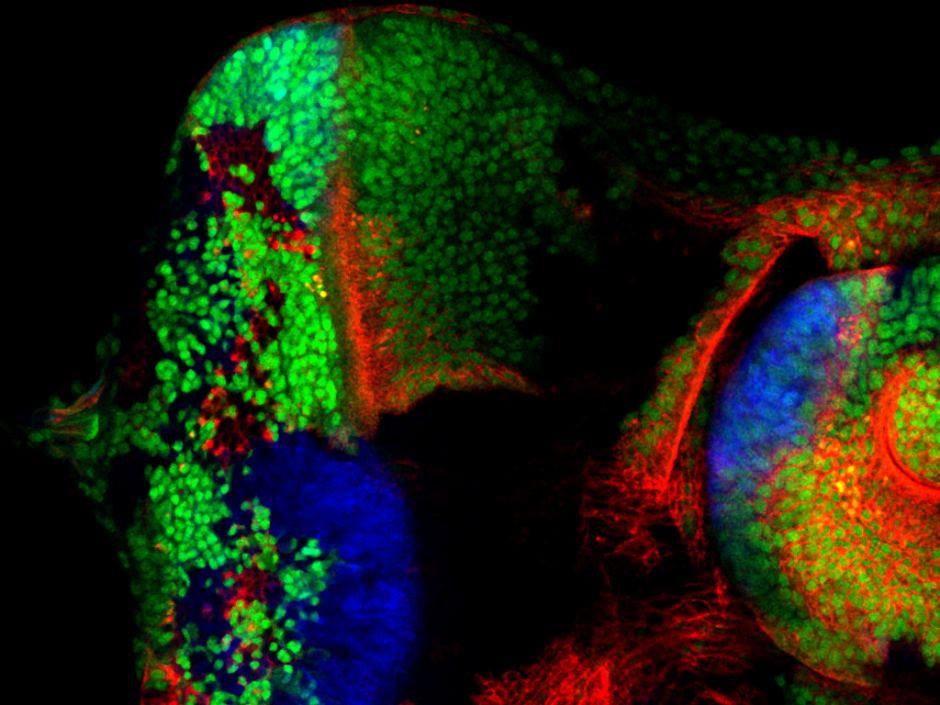

Image: A microscopic image of a fly eye showing the mutation, in blue and red, which was corrected and the cancer reversed. Supplied: Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre