About 5 minutes into Tuesday’s press conference describing the first U.S. Ebola diagnosis, Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), segued from talk of on-the-ground aid in Africa by saying, “But ultimately, we are all connected by the air we breathe.”

That comment—meant to express the importance of controlling the spread of the virus both overseas and in the United States—compelled Edward Goodman, an epidemiologist at Texas Health Presbyterian Hospital Dallas, who spoke after Frieden, to clarify: “Ebola is not transmitted by the air. It is not an airborne infection.”

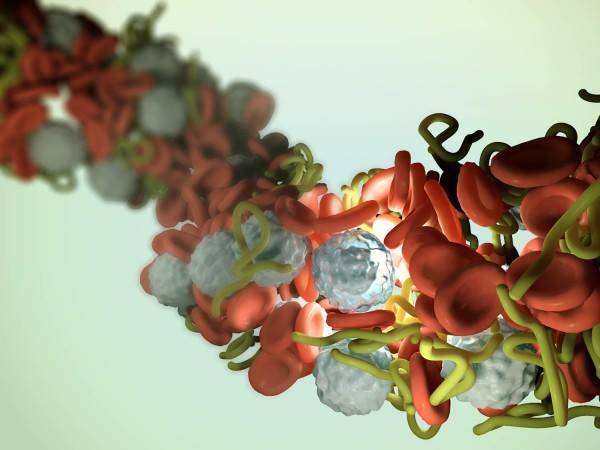

Many news stories have driven home the point that the virus is mainly transmitted through direct contact with bodily fluids, people are only infectious when they develop symptoms, and it’s unlikely that Ebola will evolve to become airborne.

But there’s precious little data on some other practical questions: Which bodily fluids harbor the virus? Does it linger on objects touched by an infected person?

Hard data are scant in large part because Ebola outbreaks have been sporadic, and because every epidemic before the current one ended before even 500 people became infected. A few epidemiologic studies have interviewed infected people and their close contacts and clarified that it does not spread through the air. The studies also suggest that the main routes of transmission include touching an infected person, sharing a bed, and of course contact with bodily fluids. Funerals of Ebola patients also presented extremely high risks because of rituals that involve touching the body, group hand-washing, and communal meals.

One study examined skin from people who died from Ebola and suggested that sweat may play an important role. “One possible explanation for the role of direct physical contact in transmission is the presence of abundant virus particles and antigens in the skin in and around sweat glands,” the authors concluded. But the most comprehensive analysis done to date notes that risk factors differ depending on the stage of disease, and that people at late-stage disease or death are far more likely to transmit the virus.

A crucial 2007 paper, published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases, offers perhaps the best indication available of where the risks lie, and where they don’t. It analyzed samples from confirmed cases during a 2000 outbreak in Uganda, including people who were acutely ill or recovering. It also looked for the virus on objects, such as desks, walls, and gloves, in an Ebola isolation ward. The study’s numbers are small, but it’s the most detailed analysis published to date.

Source: Kelly Servick, Jon Cohen, Science Insider

Full Article with Graphs: http://bit.ly/1x6ZFux