A virus may be to blame for the development of celiac disease, researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPMC) reported in the journal Science. The culprit is the reovirus, a common and otherwise harmless infectious agent, which triggers the immune system response to gluten that results in celiac disease.

A virus may be to blame for the development of celiac disease, researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine (UPMC) reported in the journal Science. The culprit is the reovirus, a common and otherwise harmless infectious agent, which triggers the immune system response to gluten that results in celiac disease.

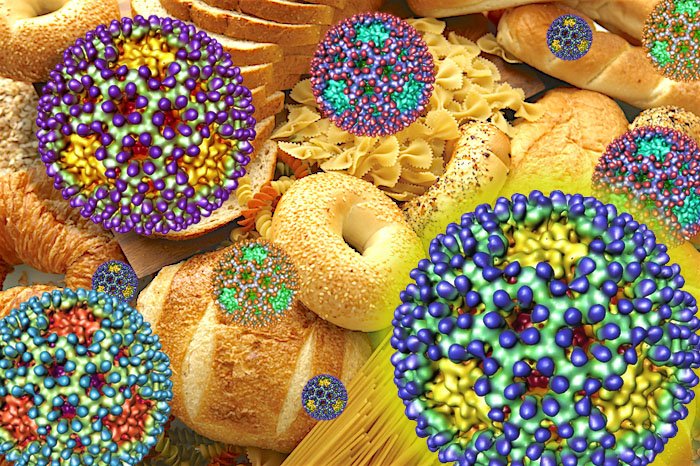

One in 133 people in the United States suffer from celiac disease, an autoimmune disorder. It often goes undiagnosed, and it is thought that only 17 percent of those one in 133 people know they have the disease. Celiac disease is caused by an inappropriate immune response to the protein gluten, found in foods such as wheat, rye, and barely. This response leads to damaged lining of the small intestine. No cure exists for the disease, and people who have it must follow a gluten-free diet to avoid symptoms and intestinal damage.

This new study adds to evidence that viruses are involved in the development of autoimmune disorders such as celiac disease and type 1 diabetes.

“This study clearly shows that a virus that is not clinically symptomatic can still do bad things to the immune system and set the stage for an autoimmune disorder, and for celiac disease in particular,” said study senior author Bana Jabri, MD, PhD. “However, the specific virus and its genes, the interaction between the microbe and the host, and the health status of the host are all going to matter as well.”

Digesting gluten is a challenge even for people without celiac, because it is a dietary protein naturally poorly digested. Therefore, it’s more likely to trigger an immune system reaction compared with other proteins. However, it’s not known for sure exactly how gluten triggers an inflammatory immune response. Past studies have found that IL-15, an inflammatory protein known as a cytokine, is overactive in the intestinal lining of celiac disease patients and it lowers the oral tolerance to gluten. Even so, not all celiac disease patients overexpress IL-15.

The current study shows that intestinal viruses can cause the immune system to overreact to gluten, leading to the development of celiac disease. The study authors used two different reovirus strains to show how genetically different viruses can have unique effects on the immune system. When given to mice, one common human reovirus strain caused an inflammatory immune response and the loss of oral tolerance to gluten. However, another closely related but genetically different strain had no effect on gluten tolerance.

“We have been studying reovirus for some time, and we were surprised by the discovery of a potential link between reovirus and celiac disease,” said one of the study authors, Terence Dermody, MD. “We are now in a position to precisely define the viral factors responsible for the induction of the autoimmune response.”

The researchers also observed much higher levels of antibodies against reoviruses in people with celiac disease compared with non-celiac patients. The celiac patients with elevated levels of reovirus antibodies had much higher expression of a gene involved in the loss of oral tolerance to gluten. This suggests that infection with a reovirus can permanently damage the immune system and lead to a later autoimmune response to gluten.

The findings indicate that infection with a reovirus could be an important triggering event for developing celiac. The timing of exposure could also matter. In the United States, around six months of age, babies are weaned from breastfeeding and usually eat their first solid foods, which often contain gluten. At this time, children whose immune systems haven’t matured are more vulnerable to viral infections. For children genetically predisposed to celiac disease, combining an intestinal reovirus infection with the first exposure to gluten could create the perfect storm for developing celiac.

“During the first year of life, the immune system is still maturing, so for a child with a particular genetic background, getting a particular virus at that time can leave a kind of scar that then has long term consequences,” Jabri said. “That’s why we believe that once we have more studies, we may want to think about whether children at high risk of developing celiac disease should be vaccinated.”

The next step? The researchers are investigating the possibility that other viruses can have similar effects.

The study adds to past evidence that viral infections can lead to complex immune-mediated diseases. It suggests vaccines targeting viruses infecting the intestine could protect children predisposed to celiac and other autoimmune disorders.

Source: Romain Bouziat, Reinhard Hinterleitner, Judy J. Brown, Jennifer E. Stencel-Baerenwald, Mine Ikizler, Toufic Mayassi, Marlies Meisel, Sangman M. Kim, Valentina Discepolo, Andrea J. Pruijssers, Jordan D. Ernest, Jason A. Iskarpatyoti, Léa M. M. Costes, Ian Lawrence, Brad A. Palanski, Mukund Varma, Matthew A. Zurenski, Solomiia Khomandiak, Nicole McAllister, Pavithra Aravamudhan, Karl W. Boehme, Fengling Hu, Janneke N. Samsom, Hans-Christian Reinecker, Sonia S. Kupfer, Stefano Guandalini, Carol E. Semrad, Valérie Abadie, Chaitan Khosla, Luis B. Barreiro, Ramnik J. Xavier, Aylwin Ng, Terence S. Dermody, Bana Jabri. Reovirus infection triggers inflammatory responses to dietary antigens and development of celiac disease. Science, 2017; 356 (6333): 44 DOI: 10.1126/science.aah5298