Poor oral health is a risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease. What’s not clear is whether gum disease causes the disorder or is merely a result — many patients with dementia can’t take care of their teeth, for example. Now, a privately sponsored study has confirmed that the bacteria that cause gum disease are present in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s, not just in their mouths. The study also finds that in mice, the bacteria trigger brain changes typical of the disease.

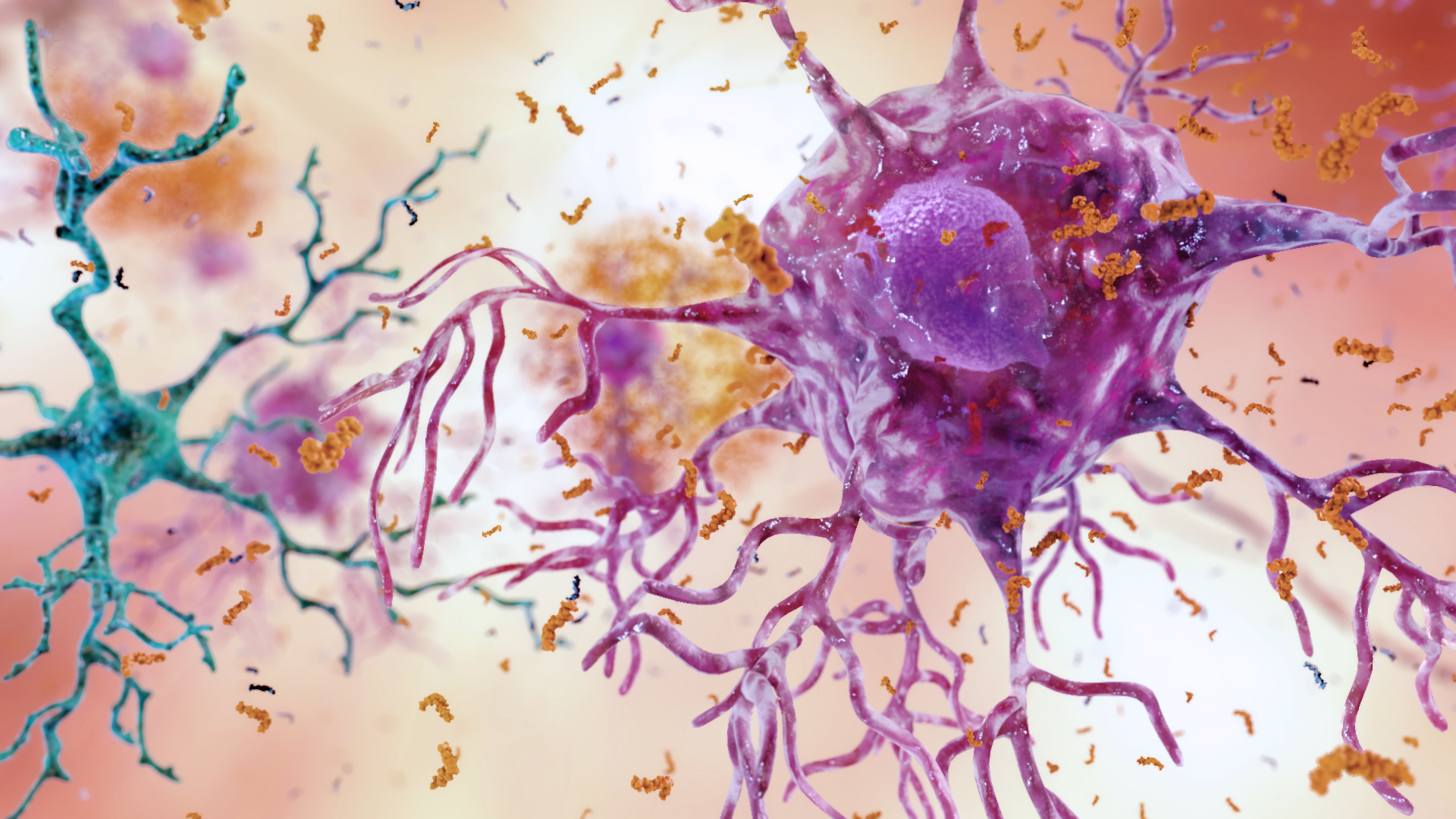

The newly published study suggest that Porphyromonas gingivalis, a bacterium commonly associated with chronic gum disease, is capable of traveling from mouth to brain where it triggers chemical changes that damage cognitive function.

According to the paper, while other infectious agents have been implicated in the development and progression of Alzheimer’s disease, the evidence hasn’t been convincing.

However the researchers now have strong evidence connecting P. gingivalis and Alzheimer’s.

P. gingivalis, best known for causing periodontitis, is an inflammatory disease that steadily eats away at gums and bone that support teeth, due in part the production of gingipains, powerful enzymes that chop up other proteins. The bacteria has also been previously linked to the chronic inflammatory disease, Rheumatoid arthritis (RA).

In recent years, scientists have begun to tentatively link Alzheimer’s disease to P. gingivalis infection — raising the possibility that these mouth-loving microbes might have the capacity to set up shop in the brain.

In the new study, a team led by Stephen Dominy and Casey Lynch of Cortexyme, a San Francisco-based company developing Alzheimer’s therapeutics, found bacterial gingipains in the brains of over 90 percent of a group of more than 50 deceased Alzheimer’s patients.

And the more gingipains an individual had, the more that brain showed chemical signs of deterioration, including the accumulation of a protein called tau.

Under normal circumstances, tau helps neurons maintain structural integrity. But in brains progressing toward Alzheimer’s, this protein can undergo abnormal chemical changes and tangle into knots inside brain cells, compromising their ability to send each other signals.

When the researchers introduced P. gingivalis into the mouths of eight mice, they found that the bacteria migrated into all of their brains within a few weeks.

In response to the infection, the mice also seemed to be boosting production of a protein called amyloid beta. Like tau, amyloid beta occurs in the brain naturally but behaves abnormally in Alzheimer’s patients, forming sticky aggregates outside of cells.

What amyloid beta does under normal circumstances isn’t well understood. But some researchers, including Dominy and Lynch, believe that it plays a role in the immune system, and is manufactured when the body senses an unwanted microbe. “It’s kind of like the body sending out a little net, saying, ‘I’m going to trap these bacteria,’” Singhrao says.

While that might sound like a good thing, amyloid beta’s protective powers might ultimately cause harm. When P. gingivalis infiltrates the brain, amyloid beta could be cued into overdrive — and if these microbe-trapping nets aren’t cleared out of the way, they might glom together, clogging up lines of communication between brain cells. As with the case with tau, these cellular roadblocks could ultimately nudge the brain in the direction of dementia.

But Dominy believes there’s more to the issue than an overactive immune system. “We think the gingipains are really the culprit here,” he says. “They’re damaging the brain directly.”

In keeping with this, when the researchers exposed mice to a strain of P. gingivalis that lacked its destructive gingipains, the rodents suffered fewer Alzheimer’s-like changes in their brains. And when P. gingivalis-infected mice were treated with Cortexyme’s new anti-gingipain drug, fewer bacteria invaded the brain and there was less accumulation of amyloid beta.

Cortexyme’s drug is already in human clinical trials, and Lynch says the early results are encouraging. Regardless of the outcome for this particular drug, however, the case on Alzheimer’s is far from closed. Stronger links between oral infections and Alzheimer’s still need to be established in humans, says Allison Reiss, an Alzheimer’s researcher at New York University’s Winthrop Hospital who was not involved in the new study. After all, she says, while the study’s findings in mice are encouraging, what happens in rodents isn’t always recapitulated in humans.

Even if these results pan out in human populations, not all Alzheimer’s patients are the same, says Ming Guo, a neurologist and Alzheimer’s expert at the University of California, Los Angeles’ Brain Research Institute who was not involved in the new study. It could turn out that bacterial infections are just one possible avenue for dementia and mental decline to progress in what is a notoriously complex disease.

“Alzheimer’s is a complex disorder, not a one stop shop,” Reiss says.

Many other questions remain. It’s still not entirely clear how P. gingivalis breaches the brain’s barriers in mice or humans—or how risky it is to have these bacteria living inside you in the first place. Numbers vary, but P. gingivalis might live in the mouths of up to 40 percent of healthy individuals, and many of these individuals will not suffer adverse effects.

In other words, a P. gingivalis infection doesn’t guarantee Alzheimer’s, and there’s no conclusive evidence that all Alzheimer’s cases stem from P. gingivalis. Regardless, Singhrao says, it doesn’t hurt to practice good oral hygiene — if not for your mind, then at least for your mouth.

Source: Stephen S. Dominy et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer’s disease brains: Evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors. Science Advances, 2019 DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aau3333